There is nothing wrong with striving to do things right and perfectly. It depends on how often you...

Semi-annual values-based review

Reading Time: 4 minutes

Most people use the end of the year as a time for reflection, planning, and assessing how things have been for them. I personally like to set mini-quarterly reviews on my schedule along with reset time and spend more time in a mid-year review. I very much welcome a moment to pause, reflect on what has happened, what’s next, and how I want to live my life.

So, instead of looking strictly at goals or accomplishments, I like to reflect on the:

- The actions I took – whether they took me closer to or further away from my values

- Internal struggles I had with some ways of thinking and feeling

- Learnings I had in different areas of my life.

- Check any themes that have emerged

That’s why I called this process “values-based year review,” and you can do it any time that works for you. More than having a specific time to complete this review, it is more important to reflect on how you have been living your life, what makes it challenging, what happens under your skin when pursuing what matters, and what you need to do next to be the person you want to be.

If you want to do your own values-based mid-year review, here is a 21-page template you can use; it includes a description of 9 areas, a values thesaurus, a values dashboard and reflective prompts for each area in your life.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD YOUR VALUES-BASED REVIEW TEMPLATE

As I reflected in the last couple of moments, below are the theme, highlights, and key learnings that emerged for me.

Chaos and connection

2020 and the beginning of 2021 were very challenging times. The pandemic unfolded, Black Lives Movement, a presidential election in the United States, unexpectedly losing close friends, and my health being affected made it one of the hardest years and also, one of the most compassionate ones.

You see, as a full-time psychologist, specialized in fear-based struggles – I’m sure many of my colleagues relate to this – we breathe and live situations related to all types of fears every single day. But, when you have an insurmountable amount of stressors around you, those experiences augment exponentially.

Yet, for over 12 months we all did our best to show up to the people we work with and care about while acknowledging our vulnerabilities, limitations, and common humanity. If you’re a provider in mental health reading this newsletter, my sincere appreciation for all that you did the last couple of months!

In the midst of all the political, environmental, social, cultural, and economic chaos we went through, in one way or another, my connections with others were also reinforced, for the most part, revitalized in some cases, and renewed in others. It was in those catching-up moments that I realized, once again, that life is all about connecting with others and creating memories with the ones we love. It was in those moments that I experienced “chaos and connection” co-existing next to each other.

Key learnings

- Savouring every moment that comes my way allows me to find new rhythms

- Life is much more manageable when I’m around people that get me

- Showing up to my friends as the best I could is essential to growing my friendships.

- Being flexible when unexpected things happen is fundamental to keep doing what matters.

- I undeniably have a low tolerance for bureaucracy and institutional fakeness.

- Being self-employed is one of the best things I have ever done in my life.

- Being real with people is fundamental to building long-lasting relationships

Highlights

My thirst for creating resources and owning my content has grown tremendously. Here are the highlights from the last 6 months and some from 2020 – 2021:

- I discovered Ness Labs and for the first time, got exposed to a group of kind, bright, and incredible collaborative people from all over the world, interested in science-based ideas and related fields. It was absolutely mind-blowing and still is, that this group is non-hierarchical and non-clicky by nature; it’s 100% collaborative.It doesn’t matter which school you went through, who you’re associated with, who you collaborated with, what’s your expertise, or who is in charge.Ness Labs is a culture of collaboration.You know something that could be helpful to another person, you offer it; you have an idea that could be helpful to another person you offer it. You don’t know something, you ask for it. You don’t need to be the expert but a co-creator of knowledge. And trust me when I say that this was mind-blowing to me, I mean it. While I’m not an academician, I have been part of academic and professional environments that, as nice as they are, all are structures around hierarchy, seniority, and under-spoken clickiness.

- My book Living beyond OCD got published and with it, a comprehensive resource to tackle Obsessive Compulsive Disorder using Acceptance and Commitment Skills.

- Co-authored a book on process-based therapy that will be released in 2022.

- Finished a manuscript for people prone to high achieving and perfectionistic actions.

- Collaborated in two research projects looking at the effectiveness of the interventions described in two of my books (papers have been submitted already, yay).

- Got a bike – a lifesaver and mood buster.

- Hosted many zoom calls with friends all over.

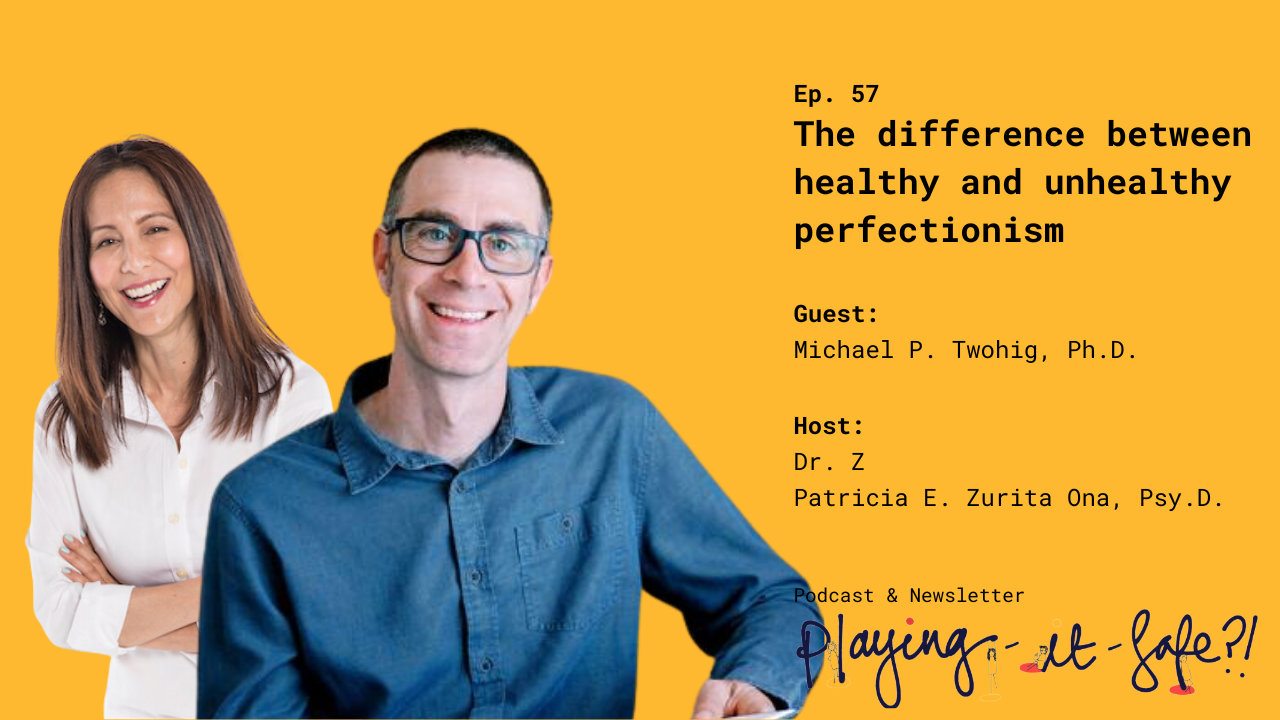

Playing-it-Safe: A project from the heart:

The question of “how can we get unstuck from ineffective playing-it-safe moves so we can live a meaningful, fulfilling, and purposeful life?” is fundamental in my work, and my thirst for answering it has grown significantly.

Playing-it-safe has been one of the highlights of what has been a weird year.

In 2020, I launched the Playing-it-Safe newsletter and the Playing-it-Safe podcast without knowing how these projects were going to be received. For the last few months, I’ve sent out this newsletter every Wednesday in an effort to share research-based skills derived from behavioral science, Acceptance and Commitment ‘Therapy, reflections, and resources related to fear-based struggles.

You have witnessed the evolution of my style in the podcast as it’s a new way of creating resources for me and have heard me trying different formats. Little by little, right?

The response from all of you to these resources has been bigger and much better than I could have expected. Thank you for keeping in mind these resources!

It’s my goal that Playing-it-safe continues to grow and get better in the next months. I have some exciting plans in the works for it. Stay tuned!!!

Thank you for spending some time with me each week.

I think learning to relate skillfully to fear-based emotions is a very important topic and I’m excited to continue creating more resources about it in the coming months. What am I missing? Is there something that you’d like to see me write about in the future? If so, please send me an email at doctorz@thisisidoctorz.com.

As always, if you think a friend of yours would be interested in fear-based reactions, please share this newsletter with them!